Phone Number: (917)-225-0836

Email Address: kirkwesleymail@gmail.com

I had the privilege to testify before the Higher Education and Employment Advancement committee in support of bill PHB-6883- An Act Concerning A “Correction To College” Pipeline for Youthful Offenders- a bill that I wrote the language for. I shared with the committee the need and importance of this bill and how it can reshape juvenile justice in the state of Connecticut as we know it. I told them my personal story and how I struggled to put my life together after being released from prison at 19 and that if it wasn’t for my sheer will and determination I would not have been before them. At the end of my testimony, a committee member said, “Kirk, you made my day. Thank you for being here and for helping us to understand why this is so important.” I said, “you’re welcome,” then they clapped for me.

*This system has been designed to destroy the lives of people like me and only a new system, a new way of thinking, will help move our communities forward. I was the only one who spoke on behalf of this bill but 1 will always chase 1,000. Don’t get it twisted though, I’m not a politician- I’m just a real one who got free, learned the game, and, in the spirit of my ancestors, I’m coming back for the tribe. I’m confident that this bill will be passed, but this is already a win: for me and the culture. Selah. 💯🙏🏿✊🏿 @ Connecticut State Capitol

People have been asking me- “But what’s after the rally?’

My response is simple- Ask yourself that question… After the rally 2 years ago, I was quoted saying “we can rally all we want but we have to take measures.. and it starts with the youth.” In that time I’ve been a foster parent and have given over 30 young people means for lawful employment. What have you done individually to help change the cycle in our community? Ask yourself that question and take a look at the man or woman in the mirror.

BRIDGEPORT — Back in high school, while walking home along Hawley Avenue, Jerome Geyer said he was stopped and questioned at least three times by police looking for a burglar.

One night, while driving home from Fairfield, he can recall being pulled over by that town’s police and asked if he had weapons or narcotics in the car. When he said no, the officer replied: “You do know marijuana is a narcotic.”

On Wednesday, standing in the courtyard of Housatonic Community College, the 27-year-old with dreadlocks recalled trying to stay calm and cordial then.

“But it infuriated me,” he said. “I don’t even do drugs. How does that relate to me?”

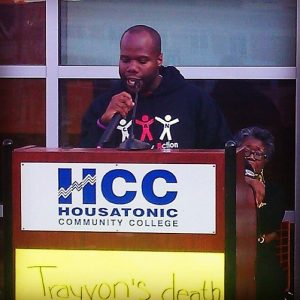

Geyer was one of about 300 people at HCC Wednesday evening for the “I Am Trayvon Martin Rally,” which featured speakers such as Bridgeport Mayor Bill Finch, an aide to U.S. Rep. Jim Himes and Yohuru Williams, director of black studies at Fairfield University.

The speeches, placards and conversation that filled the event decried the sort of racial profiling that has jumped onto the nation’s radar since the 17-year-old Florida resident — who was wearing a hooded sweatshirt, and carrying a bag of Skittles candy and an Arizona iced tea — was slain by a neighborhood watch volunteer who has yet to be charged.

The event also centered around how the Bridgeport community can curtail the mostly black-on-black youth violence that has claimed dozens of lives here in recent years.

The grassy quad beneath the school’s parking garage started filling just before 5 p.m., with high school and HCC students — some wearing backpacks, many in hoodies — parents, politicians, police and professors. It lasted nearly two hours.

“I had high expectations, but the turnout was even higher,” said Kirk Wesley, 26, the HCC student who called for the event six days earlier by posting on Facebook. A Bassick High graduate and president of the Community Action Network, a student group dedicated to improving the city, Wesley left the rally excited, but cautious.

“We can rally as much as we want. But we need to take measures, and it starts with the youth.”

Samuel Conway, 26, watched from the back of the crowd. At 6-foot-2 and more than 300 pounds, he imagined himself a big potential target like Martin. Every time he turns on the news, he said, he hears of police searching for what he considers the worst sort of stereotype, a black man in his favorite type of sweatshirt.

“I wear hoodies because I don’t like carrying an umbrella,” he said, staring off across the quad. Quietly, he added: “It could have been me.”

April Barron, 44, arrived with about 15 of her relatives, wearing shirts and necklaces displaying pictures of her son. At 27, Iroquois Alston was gunned down last summer in Norwalk. The killer is still at large. Barron’s son was set to start psychology classes at Housatonic last September, she said. Now she looked out at many of the young men and women who could have been his classmates.

“The violence has to stop, and it’s mainly our kids killing each other,” she said. “I will do anything to support anything that’s positive.”

While she spoke, Ahlaam Abdul, 21, took the stage. The Bassick graduate had just finished teaching a creative writing class at Thomas Hooker School. On her way back to HCC, where she now studies, she had enough time to compose a nearly 600-word poem for the event. She climbed on stage and read from her phone:

“When black death is widespread, when the community is misled, and the government is white led, when the system doesn’t let us get ahead, when words of justice go unsaid, when hatred is spread instead, I wonder about this country we live in sometimes … .”

Kirk Wesley got up early the day of his speech, mostly because he hadn’t slept well the night before.

He knotted his thick violet tie, climbed into his charcoal suit and headed out to the corner. When his bus rumbled to a stop on North Avenue, he exchanged a couple of dollars for a ticket and found a seat.

The bus made its way across the city, pulling up Stratford Avenue toward the billiards hall where one night last spring someone was murdered. Wesley got out there and made his way a final block to the school.

In the cafeteria, he sat before the stage, before the banner that said: “Congrats Class of 2012.”

In a moment, about 70 eighth-graders would file in, including 10 boys Wesley had mentored since January. In weekly sessions, he’d hoped to protect them from the traps that snared him as a teenager, nearly ruining his life. Now he had a larger audience and one final chance to make his point.

As the cafeteria filled with people, Wesley clutched his manila folder with the speech inside.

“I’m a little nervous,” he said.

Jettie S. Tisdale School opened in 2008, a $48 million project that created a sanctuary of sorts for elementary and middle schoolers growing up in this city’s rough East End.

Step in the door, and it feels like a portal to Westport. Sunlight pours in through towering windows; hallways burst with optimistic signs.

“Welcome to our school,” states a banner hanging in the foyer. “Where children and learning come first.”

The cheerfulness, though, is in large part an act. A liquor store lurks a block away, the nearest business. Sneakers hang from power lines right down the road. An “End of School Zone” sign is tagged with blood-red graffiti. Police sometimes review the school’s security cameras, investigating a late-night shooting, mugging or rape.

“It’s a high-risk environment,” said Carmen Dixon, who has served as principal of a Bridgeport school for 23 years now — and who just wrapped up her first at Tisdale.

Asked about her eighth-graders, she said she can’t help but worry about the ones who get in trouble.

“What’s going to happen when they get to high school?” she said. “I fear they’ll drop out, and then they can’t work. How are they going to live? How will they be productive citizens?”

“I can’t tell you,” she adds, “how many of my students have been killed.”

In January, Wesley phoned Tisdale in a fit of passion. He wanted badly to work with the school’s most at-risk boys.

The guidance counselor, Cheryl Shoulders, invited him in for an interview. She heard out his story, listened to his vision and promptly began asking teachers to pick out the right students.

“They’re just kids,” Wesley likes to say. But that doesn’t mean they’re always innocent. In late winter, one of his students led a group assault on a young boy and stole his bike. He was later arrested and consequently suspended. In fact, at many of the group’s meetings, the topic of who’s suspended — thus not at the meeting — comes up.

At a morning session in late May, arrayed in the school’s upstairs teachers’ lounge, Wesley asked them to describe where they see themselves in 10 years.

A couple of them said they hope to be in college. They weren’t sure what they’d study, but they knew it’s important to secure a job that can support a family. Wesley smiled at that.

One student mentioned something about his girlfriend. Wesley, who can be quick with a scowl, told him to be careful: Too many teenage boys get their girlfriends pregnant, he said, without really grasping the consequences. The boy smiled sheepishly and turned his head.

One student hadn’t said much of anything. To Wesley’s knowledge, he hadn’t gotten in trouble this semester, either.

“Sometimes, I’m not even sure why you’re here,” Wesley said.

“I have bad anger problems,” Andre, 15, answered.

Then there was Tariq, a tall 14-year-old, who said he hopes to play professional basketball. A couple of students laughed at that, which made Wesley angry.

“Don’t you guys know what crabs in a barrel do?” he asked. “Whenever one tries to make it out, the others keep pulling it back.”

In midspring, Cheryl Shoulders invited Wesley to be guest speaker at the eighth-grade graduation.

He jumped at the chance. At home, he likes listening to old recordings of Martin Luther King Jr. Here was a chance to speak in front of several hundred people and to leave an impression on the potential future leaders of Bridgeport.

But what, he had to decide, can you say to prepare eighth-graders for all that comes next? What about in a high-crime area, with underperforming schools?

Wesley wanted to focus on what was possible, not dwell on what to avoid. He settled on what he wouldn’t tell them:

How he moved here from New Jersey at 15, as an honors student.

How he lost all concern for school at Bassick and his grades plummeted.

How he got suspended three times his senior year, but still managed to get into the University of Connecticut.

How he dropped out his first semester.

How one night, three weeks later, he pointed a gun at the head of a Chinese food deliveryman. How he stole the man’s car, held up a Subway, forced the worker to lay face down on the freshly mopped floor.

How he spent nearly a year in prison.

Wesley was 19 when his mother drove him home, just before Thanksgiving 2004. His heart raced when she pulled into Bridgeport. He made her let him out a mile away. He wanted to walk the last stretch as a free man.

Nine months away had seemed like an eternity. He stopped at the music stand at Getty Gas station to find out what songs he’d missed. He bought a couple of CDs from his neighbor, a man about his age, named Greg Thomas.

Over the next six years, Wesley and Greg grew close. At first, Wesley struggled to hold a job. He installed pools. He replaced roofs. He built fences. Off the clock, he often sat on Greg’s porch. They would talk late into the night about what they wanted in life.

Eventually, he returned to school. After his Bassick and UConn debacles, it took him a while to feel confident in the classroom. But when he did, he wanted to get more involved at Housatonic Community College. He helped create a student group called Community Action Network. The idea was to get to know fellow students by heading into the community, cleaning up streets and mentoring kids.

In 2010, Wesley graduated with an associate’s degree, and he’s grappled with what to make of himself ever since. He knows there are jobs out there, but he hasn’t landed one he loves. He knows if he simply takes one that pays, he might be able to get a car and move out of his mother’s apartment. But he hasn’t done it. He likes listening to the Martin Luther King speeches in his room, and he feels a rush when he watches a DVD of himself, speaking this past winter before his church about black history month. Maybe, he tells himself, if he plays his cards right …

Last fall, things got rough. His gig tutoring students at Housatonic ran out. He had a lot of free time. Luckily, he won a scholarship at church that would pay for one more semester at Housatonic. He signed up for government classes, hoping to get the ball rolling on a career as a community organizer or politician.

One day, he thought, he could help make Bridgeport a better place.

On New Year’s Eve, he left the evening church service and was headed home when he ran into Greg Thomas. They talked, briefly, about their plans for the night. Wesley was staying in, he said. Greg was going to celebrate.

Three hours after midnight, Greg was shot dead on his front steps.

Days later, Wesley placed an impassioned phone call to Tisdale.

The day of his final mentoring session, as the bus cut across Bridgeport, Wesley was jittery.

He’d been repeating himself for four months. Now he wondered if anything he’d said was sinking in. He was growing increasingly pessimistic about it.

They had ordered pizzas for that day’s group. Wesley was considering holding it hostage. No food, he decided, until they answer questions right.

When he arrived, the news at front office didn’t help things. About half his group, he learned, wouldn’t walk across the stage at graduation. One had been suspended for cursing at a teacher. Others were getting punished for too many tardies.

The news cast a pall over the first few minutes of the session. But the students’ responses were reassuring.

“What’s one thing we discussed in this group?” Wesley asked.

“Our futures,” someone said.

“Reading books and stuff,” said another.

“Where we’ll be 10 years from now,” said a third.

When they were asked if anything they had discussed made an impact on their lives, one student said he’d stopped playing so many video games. It was just a waste of time, he said. Another said he’d skipped a recent Friday night party because he knew he’d probably get in a fight there.

Wesley asked how they felt about graduating.

One said he’d do all his schoolwork in high school. Another said he’d go to prom all four years.

Wesley gazed around the room with the eyes of an older brother.

“Don’t let this be your last graduation,” he said.

The students nodded.

“All right. Let’s get some pizza.”

The sense of calm he felt lasted less than 24 hours. He couldn’t sleep the night before graduation, and now he sat nervously in the cafeteria, waiting for his chance to speak. The Tisdale students filed in, with “Pomp and Circumstance” sounding from the speakers.

When the room was filled, the principal got up and gave a short speech. She told the students that they had better graduate high school and college. She urged parents to never give up on their children.

Next came the school choir, whose members sang out a looping chorus that went, “I pray for you, you pray for me, I love you, I need you to survive.”

The valedictorian said that everyone has a destiny and is placed on this Earth to make it a better place.

Finally, it was Wesley’s turn.

He stepped to the lectern, gazed out at the rows of eighth-graders, and then their parents and friends. He asked them all to applaud themselves, hoping this would capture their attention.

“Some of you have visions of being a lawyer, a doctor or a teacher,” he finally said. “Some of you even have visions of being a professional athlete. Hold on to those visions. Nurture them. Grow them and in time you will reap the harvest that comes with being steadfast.”

Recently, he recounted, he had an intimate conversation with a friend. He had said he wants to one day own a home in Black Rock and a weekend apartment in Manhattan. He said he also wanted a condo in Miami. And a beach house in Puerto Rico. And a family compound in Jamaica.

His friend shook his head, and he guesses it’s always good to dream.

“This isn’t a dream!” Wesley boomed into the microphone. “This is a vision I have for myself!”

Parents chuckled; a man in back of the cafeteria nodded his head.

“You have got to be completely wrapped up in the vision you have for your life,” Wesley said.

You need the discipline, he said, to shut off your X-Box and study for your big test, even if it’s two weeks away.

You need the determination, he said, to believe in yourself, even when everyone around you can offer only doubt.

You need the dedication, he said, “where it doesn’t matter what no sweet talking boy said to you. You’re not going to let no one steer you off track of the goals that you have by getting you pregnant.”

He paused.

“Because the vision you have for yourself is much bigger than Stratford Ave.!”

The cafeteria filled with applause, and a scattering of parents rose to their feet.

When the ceremony ended, everyone headed out to the courtyard, and Wesley paced around in his suit, scanning for his students.

Cheryl Shoulders came up first, posing with him for a picture. Then came a 46-year-old to shake his hand.

“That was a great speech, I was inspired myself,” he said. “I don’t think you can be any more positive in Bridgeport.”

Next, Tariq’s mother found Wesley, and pulled over her son. They smiled for a picture. She recalled how Tariq had come home after the first day of the group, saying it would be a waste of time. She recalled how he’d come home a few weeks later, saying, “That Wesley really knows what he’s talking about.”

The crowd thinned, and it was almost time for Wesley to figure out how he was going to get home. But before he could go, another one of his students stepped up to his side.

It was Andre, the one working through anger problems.

“Congratulations, bro,” Wesley said. “You ready for the next step?”

“I’m gonna take it all the way.”

© 2022 Designed By Digital Guider